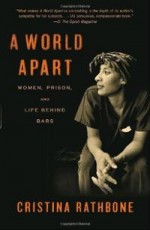

there are six matriachs: buy your Jewish feminist t-shirt today at www.therearesix.com

The t-shirt I mention in this post is available for purchase! All proceeds go to the Boston Area Rape Crisis Center, a local organization that my husband and I think is doing really important work. Wear your Jewish feminist commitment with pride. To own your very own matriarchs t-shirt, go to www.therearesix.com.

In an odd confluence of events, I’ve had occasion recently to think a lot about ancestry.

First, my husband made me an awesome shirt. (It’s in the style of this “goddesses” shirt — at least this is the first instantiation that I knew about; one of my classmates said the meme was originally from a band.) My shirt lists the six Jewish matriarchs: Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, Leah, Zilpah, and Bilhah. You can buy one here, thanks to my husband, and all proceeds will go to the Boston Area Rape Crisis Center.

When my husband and I were talking about making the shirt, his idea included just the first four women, who are indeed traditionally considered “the matriarchs.” Abraham’s wife, Sarah, gave birth to Isaac, who married Rebecca, who had Jacob, who married Rachel and Leah. The latter two women gave birth to Joseph and Benjamin (Rachel) and Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, Issachar, and Zebulun (Leah).

But Bilhah and Zilpah also gave birth to sons of Jacob whose lines would become four of the twelve tribes of Israel. The two were handmaidens of Rachel and Leah, respectively, given to the women by their father Laban on the occasion of their marriages to Jacob. Bilhah had Dan and Naphtali, while Zilpah had Gad and Asher. The tribes that these men and their brothers (and their nephews) founded ended up in Egypt as slaves to Pharoah, leading to the Exodus story that is foundational in Jewish history. If, in the logic of the Bible, patrilineal descent is what matters, then Bilhah and Zilpah deserve as much recognition as the traditional four matriarchs for their role in the creation of the Israelite people.

Of course, that’s a low bar. If we know little about Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah, we know even less about Bilhah and Zilpah. They are passed from Laban to his daughters, and then loaned out by them to Jacob. They are so considered property that it is Rachel and Leah who have the honor of naming Bilhah and Ziplah’s sons. So we’re told in Genesis 30:6, after Bilhah gives birth for the first time, “And Rachel said: ‘God has judged me, and has also heard my voice, and has given me a son.’ Therefore called she his name Dan.” Bilhah and Zilpah speak not a word in the Torah.

This issue of inclusion comes up most often in the amidah, the “standing” prayer and the most central one in Judaism. Said at every prayer service, the amidah begins with a section usually called the Avot (“Fathers”). It begins, “Blessed are you, Lord our G-d, G-d of our Fathers, G-d of Abraham, G-d of Jacob, and G-d of Isaac.” In progressive circles, one usually adds the Imahot (“Mothers”): “G-d of Sarah, G-d of Rebecca, G-d of Rachel, and G-d of Leah” — as well as adding a few other words at various places to make the prayer more inclusive.

As my friend and teacher Eli Herb says,

When Jews use the word “imahot” they mean Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah. This comes from old traditions that say there are seven ancestors, namely those four women plus Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Many Jews appended the name of the “imahot” to ritual prayer as a feminist gesture. This gesture was remarkable in its time. However, as a convert, I have never been able to figure out how to include imahot authentically. This is for the very simple reason that there are NOT four matriarchs. There are six. The two that are left out are of questionable status as “part of the tribe” because they were slaves. I do not know how any self respecting feminist/progressive Jew can continue to omit two of the imahot. Yet the vast majority of the “progressive” Jewish world, including Hebrew College, can not seem to move past the discussion of how important it was to include “THE imahot” in the amidah. We are NOT including “THE imahot,” friends. Rather we are making a dramatic statement about how we still do not know how to truly include the imahot; we still actively silence women and strangers.

Most of the time at Hebrew College, at my synagogue, and at the Hebrew school where I teach, the prayer leader includes “the” imahot. (A few of my classmates don’t, and, frankly, it irks me.) If not all/none of the imahot are included, I make sure to say them to myself. (A husband of one of my classmates tells me that there is rabbinical precedent for recognizing the six matriarchs, in Bemidbar Rabbah and Esther Rabbah.)

This year I’m in a new tefila group, the so-called “Moshiach Minyan.” We explore the way prayer can be a forum for collective liberation and how it can sustain us in our work as activists. A recent exercise saw us rewriting the Avot section of the amidah. I found this task both daunting and exciting — and in an hour, I came up with a list of names of those who made it possible for me to be me.

Blessed are you, Lord, my G-d and G-d of my ancestors. (Ancestors? Antecedents. The ones who came before.) The G-d who created those who created the world I inhabit, who have accompanied me on my journey, and who allow me to exist as I am. The G-d of Southern Baptists; the G-d of Hardy; the G-d of Homer and Socrates; the G-d of Virgil and Ovid; the G-d of the Brontes and Eliot; the G-d of Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Pushkin, Chekov, Bulgakov, and Akhmatova; the G-d of Wells-Barnett, Lorde, Rich, Sanger, and Doe.

We shared our writing with each other, and almost everyone wrote about some aspect of their inheritance, whether from parents loving or harsh, from civil rights pioneers, or from past experiences. Mine reads like a timeline of my intellectual development, and I’m not totally sure that’s what I am seeking when I say the avot and imahot section of the amidah.

Like Eli, I feel conflicted when saying this portion of the amidah. As a convert, these nine ancestors absolutely are my ancestors. And they’re not. I still feel a tiny twinge when I’m called up to the Torah and I give my Hebrew name as “Rachel Tzippora bat Avraham v’Sarah.” (“Bat/ben Avraham v’Sarah” is the traditional formula for converts, whose parents generally don’t have Hebrew names.) I don’t love being publicly marked as a convert (the only place in Jewish ritual where that happens), and I feel it’s a little disrespectful to my actual parents.

And I can feel even worse when my ancestry is questioned. I volunteer once-a-month at a nearby senior living facility, leading a short Shabbat morning service. The first time I was there, I was talking to several of the residents after the service, and one of them asked me about school and what I was studying. She then exclaimed, “You don’t look Jewish at all! You could be a little Irish girl!” And then she kept repeating it. As I’ve written before, I usually pass pretty easily, so it’s always a bit jarring when I don’t. I didn’t take the bait (if bait it was — I’m never quite sure what people want to hear when they say things like that). I just shrugged and smiled.

The issue came up again recently in an “Exploring Jewish Diversity” workshop that I took through the Boston Workman’s Circle. The class was billed as a conversation about how cultural heritage, class, race, and privilege inform Jewish identity. In the States, Jews are largely assumed to be white and Ashkenazi; Jews of color and of other cultural heritages are often ignored. We were given a list of Ashkenazi privilege to examine. Many of them describe me — and some absolutely do not. My friend who attended the workshop with me asked me if I considered myself Ashkenaz. Similarly to my feelings about the avot and imahot, I absolutely do — and yet am not fully. I learned to be Jewish in and I now inhabit an Ashkenazi Jewish world. It is my cultural heritage, one that I chose (if not that thoughtfully). But, for instance, I am obviously not at risk for genetic disorders that are prevalent in this population. And I’m still occasionally questioned about whether I’m “really” Jewish.

Ever since I was a kid, and I noticed how many people spent the majority of the High Holidays in the bathrooms smoking, and how many Jews I knew thought it was more important to wear a really large Mogen David, but not so important to be authentic in their prayers or to attend shabbat services regularly, I’ve been fairly certain what makes a real Jew. You, my friend, are a real Jew. You, like Ruth, have chosen to be part of the tribe. You have made a real commitment.

What is a Jew supposed to look like:? Please. Look in a mirror. That’s what a Jew looks like.

The issue is definitely not *my* questioning of my Jewish identity. It reminds me of a t-shirt one of mentors (a female rabbi) wears: This is what a rabbi looks like. (It always drives me crazy when stock photos of Jews or rabbis are white men with long beards and black hats, as if that’s the only way there is to be Jewish.) I know that I am what a Jew looks like!

Excellent! I co-lead a feminist, non-zionist havurah in Philly (going on for nearly 7 years now), and we’ve included Bilhah and Zilpah since our first service. As a raised-working class convert to Judaism, I’ve always added their names into the amidah, mumbling quietly, because, honestly, they feel more like my personal imahot.

I’d love to know more about your tefillah group. Fringes services follow the outline of the shabbat morning service, but rather than most of the liturgy we use poetry, and beautiful, long, singing. Our founding motto was: prayers that sing, songs that pray. And of course social justice has been integral to our practice as well. My email is battzedek@gmail. com. Let’s connect and share stories and resources! We just started a website for Fringes, so there’s not a lot up, but nearly all of our past services are there as downloadable PDFs: fringeshavurah.wordpress.com

Thanks for this information! My tefila group may or may not be useful to your project, but let’s be in touch. I look forward to hearing more about Fringe!

Thank you so much for sharing these reflections, Salem – really thought-provoking. Just to begin, I was wondering if you had the midrashic references on hand, I would really love to look them up 🙂

Here you go!

במדבר רבה (וילנא) פרשת נשא פרשה יב

יז ויביאו את קרבנם לפני ה’ שש עגלות צב וגו’ שש כנגד ששת ימי בראשית שש כנגד ששה סדרי משנה שש כנגד אמהות אלו הן שרה ורבקה רחל ולאה בלהה זלפה

אסתר רבה (וילנא) פרשה א

וכה”א שש מעלות לכסא שש כנגד ששה רקיעים, ולא שבעה הן, אמר ר’ אבון הן דמלכא שארי טיטיון, שש כנגד שש ארצות, ארץ, אדמה, ארקא, גיא, ציה, נשיה, תבל, וכתיב +תהלים ט’+ והוא ישפוט תבל בצדק, שש כנגד ששה סדרי משנה, זרעים, מועד, נשים, נזיקין, קדשים, וטהרות, שש כנגד ששת ימי בראשית, שש כנגד שש

Also, I’m told there’s an explicit rejection of inclusion of Zilpah and Bilhah in Bavli Berachot 16a . . .

I would buy this shirt if only Leah were listed before Rachel. I totally agree that Bilhah and Zilpah should not be excluded simply because they were slaves — that may have made sense in their day, but we should not perpetuate it now. So then why perpetuate the primacy of Rachel over Leah — for no other reason than that Jacob preferred her?

Hi, Susan. Thanks for reading and commenting. The order of the matriarchs on the t-shirt is simply the order that they are named in the Torah (Rachel = Gen. 29:6, Leah = Gen. 29:16).

Are these shirts still available? The link isn’t working for me. Thank you!

Sorry, they’re no longer available. It was a limited run.